I’ve recently presented an online ‘masterclass’ on Technology in Worship for leaders in the NSW-ACT Synod of the Uniting Church in Australia. It was a 2 hour session facilitated by Rev Dr Niall McKay who is in a resourcing role with the synod. Presenting this stuff online is tricky, because it really needs three dimensional space for demonstration. I’ve been leading various kinds of sessions, usually on multimedia in worship, for about 20 years. It was fascinating to look back and see how my input has changed over the years. Back in the late 1990’s I started studying for a Masters in Communication with the University of Southern Queensland, focusing on digital communication, learning and publishing. At the same time I was learning ‘on the job’ with various projects, as well as teaching at VET Certificate level at the Horsham Learning Centre. The Masters didn’t get fnished and became a Grad Cert (just short of a Grad Dip. sigh.)

Most of what I do about technology/multimedia in worship is to try to reframe the questions, largely informed by the alternative worship movement our of the UK, as well as Australian and New Zealand experiements. So here’s a bit of an overview. I didn’t get to cover all of the material. But wait, there was more!

Technology as integral to worship and culture

“Technology and liturgy have been involved in mutual inter-change in every period of human history… The notion that Christian worship is unconditionally good and healthy and technology is unconditionally bad and unhealthy must also be challenged… [Both] liturgy and technology… have the potential to numb the senses, deaden the conscience, and create climates of anxiety, injustice, and despair.”

“Technology and liturgy have been involved in mutual inter-change in every period of human history… The notion that Christian worship is unconditionally good and healthy and technology is unconditionally bad and unhealthy must also be challenged… [Both] liturgy and technology… have the potential to numb the senses, deaden the conscience, and create climates of anxiety, injustice, and despair.”

Susan White, Christian Worship & Technological Change, Abingdon, 1994.

“Technology is, first and foremost, a human activity that is carried out within the context provided by God for human beings to exercise their creativity and agency.”

Heidi Campbell and Stephen Garner, Networked Theology. Baker Academic, 2016.

Peter Horsfield sees media “not as instruments carrying a fixed message but as sites where construction, negotiation, and reconstruction of cultural meaning takes place in an ongoing process of maintenance and change of cultural structures, relationships, and values.”

Peter Horsfield, “Media,” in Key Words in Media, Religion and Culture, ed. D. Morgan, Routledge, 2008.

The narrative character of human experience and worship

In the late 1970’s and early 1980’s, the Queensland Education Department’s Religious Education Curriculum Project used a three circle model for lesson design, offering three sources of information to explore in relationship with one another. It is an excellent approach which I have used frequently – not only in education design, but in thinking about worship.

In the late 1970’s and early 1980’s, the Queensland Education Department’s Religious Education Curriculum Project used a three circle model for lesson design, offering three sources of information to explore in relationship with one another. It is an excellent approach which I have used frequently – not only in education design, but in thinking about worship.

I was at a workshop at a national Christian education conference once when the presenter talked about connecting God’s Story, My Story and Our Story. That immediately clicked, and I have since used it as shorthand for the RECP approach. God’s Story = Religious Tradition. Our Story = Human Experience. My Story = Personal Experience. I approach worship and education as a dialogue or dialectic between these three. Tom Groome’s Shared Christian Praxis later became a more robust foundation to work from. This way of describing it underscores the narrative character of human experience. [There’s a lot that could have been inserted here.]

My former teacher, Prof John Westerhoff, wrote a lot about the church as a story-formed community. “The church is a story-formed community… Baptism is our adoption into a story, God’s re-creative story, which is recorded in the community’s story book (the Holy Scriptures), incarnate in the community’s life, and made present through it’s sacramental rituals, especially the Holy Eucharist. Each of us also has a story. To each community Eucharist we bring our stories and re-enact God’s story so that God’s story and our stories may be made one story… In the context of our liturgies we are initiated into God’s story and we appropriate its significance for our lives so that it might influence our common life day by day… Our most important and fundamental task as Christians is to learn God’s story.”

My former teacher, Prof John Westerhoff, wrote a lot about the church as a story-formed community. “The church is a story-formed community… Baptism is our adoption into a story, God’s re-creative story, which is recorded in the community’s story book (the Holy Scriptures), incarnate in the community’s life, and made present through it’s sacramental rituals, especially the Holy Eucharist. Each of us also has a story. To each community Eucharist we bring our stories and re-enact God’s story so that God’s story and our stories may be made one story… In the context of our liturgies we are initiated into God’s story and we appropriate its significance for our lives so that it might influence our common life day by day… Our most important and fundamental task as Christians is to learn God’s story.”

John Westerhoff, A Pilgrim People, Seabury Press, Minneapolis, 1984.

In the introduction to my book, Deeper Water, I talk about worship as immersion into God’s narrative or Story, [Click on the link to download the introduction to the book for free.]

“This is an invitations to deeper water – to open a strange story and live in its pages, to learn to sing a new song in a different land, to be seared by a burning bush, to board a weathered boat and push out into the depths. Invitations that invoke and evoke the Spirit. Jesus calls his followers to go with him to the depths, to learn from experience and encounter. The Gospels don’t read like a weekly liturgy. More like a travel journal. “Dear

“This is an invitations to deeper water – to open a strange story and live in its pages, to learn to sing a new song in a different land, to be seared by a burning bush, to board a weathered boat and push out into the depths. Invitations that invoke and evoke the Spirit. Jesus calls his followers to go with him to the depths, to learn from experience and encounter. The Gospels don’t read like a weekly liturgy. More like a travel journal. “Dear

diary, we were sent out today for two weeks without map or money.”

Presentation vs Immersion

The contrast, and hence the challenge, is for worship itself to be more than primarily presentation – an audience watching the action up the front. Sadly, most of our churches are designed this way, and most of our worship is led in this way. Just Google “church building plans” and look at the images. Hence our use of technology plays into both our architecture and our largely presentational approach to worship.

The contrast, and hence the challenge, is for worship itself to be more than primarily presentation – an audience watching the action up the front. Sadly, most of our churches are designed this way, and most of our worship is led in this way. Just Google “church building plans” and look at the images. Hence our use of technology plays into both our architecture and our largely presentational approach to worship.

This of course leads to considering worship leadership as curating an experience rather than as conducting a performance. Hat tip to Mark Pierson, Mike Riddell and Cathy Kirkpatrick’s The Prodigal Project, and subsquent books by Mark (The Art of Curating), Jonny Baker and Doug Gay (Alternative Worship) and also Curating Worship.

“What would happen to the worship I prepared if I looked at it differently? What if I saw the task not as a mechanical, logical, modernist one of putting stuff in the right order so that it ‘progressed’ through a form to give a predetermined message with an anticipated outcome, but instead saw myself more like a curator of an art gallery? A curator who considers the space and environment as well as the content of worship and who takes these elements and puts them in a particular arrangement, considering juxtaposition, style, distance, light, shade, and so on. A maker of a context for worship rather than a presenter of content. A provider of a frame inside which the elements are arranged and rearranged to convey a particular message for a particular purpose. A message that may or may not be overtly obvious, may or may not be similar to the message perceived by another worshipper… So instead of Worship-Leader, or Worship-Planner, I become an artist, a framer, a reframer, a recontextor, a curator of worship. I provide contexts, experiences for others to participate in.”

From The Prodigal Project.

It needs to be said that the foundation for this writing is not merely aesthetic, rather it is based in exploring postmodern imagination and active meaning-making as foundational for worship.

“Our knowing is essentially imaginative, that is, an act of organising social reality around dominant, authoritative images… Our context of ministry is the failure of the imagination of modernity, in both its moral, theological and its economic-political aspects… It is not, in my judgement, the work of the church (or of the preacher) to construct an alternative world… rather, the task is to fund – to provide the pieces, materials, and resources out of which a new world can be imagined…. [The] meeting of liturgy and proclamation is… a place where people come to receive new materials, or old materials freshly voiced, that will fund, feed, nurture, nourish, legitimate and authorise a counterimagination of the world.”

Walter Brueggemann, Texts Under Negotiation: The Bible and Postmodern Imagination. Fortress Press, 1993. p18-20.

Examples

I played the introduction to a worship service where a water loop was playing with some ambient music [“Lux” Track 1 by Brian Eno] prior to worship. The loop kept playing and the music transitioned to a song with vocals [Down to the River to Pray by Alison Krauss]. The song finished but the loop kept playing in the background during the Call to Worship, opening prayers and theme introduction. A different example, also based on a river is described here. I had a third example of using media to invite people into an immersive experience (Geoff Boyce’s White Lady) but there wasn’t time to show it.

Here is a list of ambient music.

So we’re talking about experiencing the story in ways that are

To use technology to create immersive worship is to mess with time – not to make worship more cluttered, but to help it be less cluttered, slower perhaps, more liminal – to think about sound as a soundtrack, and liturgy as a drama with a cinematic flow.

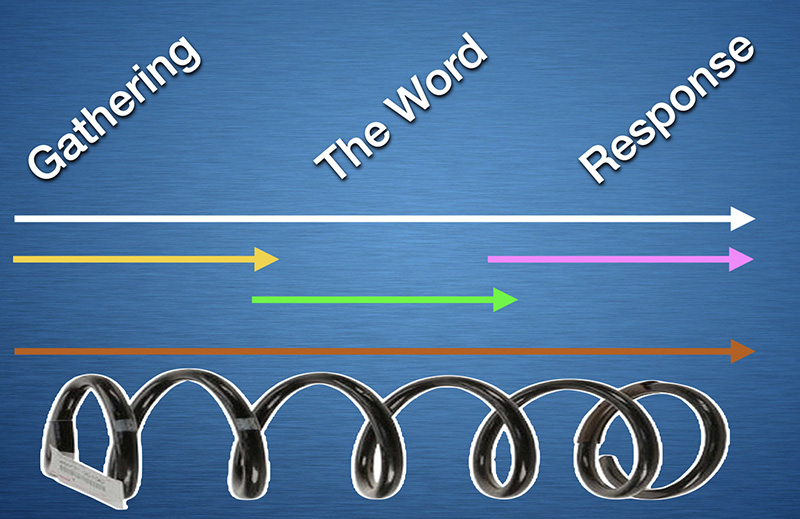

A contrast between a worship service as a kind of concert of discrete elements, each with its own media in a linear sequence:

and worship based on three broad movements with media that runs across them, including media which repeats (think of the way that a symphony or a movie soundtrack has recurring themes.)

For me, this represents a fundamental shift in the way that I think about the elements of worship, and hence the use of sound, images, symbols, participation, and even space. Of course, Word and Response can be blended / non-sequential / cyclical as well.

Anthropologist Edward T Hall talks about monochronic and polychronic societies – those in which events seem more ordered, sequential and less ‘busy’, and those in which many things happen at once, which can seem more chaotic. [See The Dance of Life, Anchor, 1984. and his other books.] For example, compare an ordered Western department store with a bustling Eastern market. While a criticism of technology in worship is that it can be used to clutter and bombard people, in fact media can be used polychronically to create a more contemplative experience. This is precisely what looping or persistent media can achieve and what curating may involve. [And just to be clear, alt worship has been highly inventive in use of space and time.]

Elieen Crowley really gets this in her little book, A Moving Word: Media Art in Worship [Augsburg Fortress, 2006] where she explores using media to lead people into contemplation. “Meditation is an art, as well as a practiced discipline. It requires structure, yet leads to structurelessness. It involves attending to the moment, yet also entering into time-out-of-time… ” How can you provide art in ways that allow people the time and space to gaze?

I described a worship service based on the Prodigal Son text where there was a cycle of visual and verbal invitations to people to “Come Home” to God – the images moved from outside a house, in the front door, and to a table with festive lights. There was also a symbolic action of a figure representing the Son being moved along a pathway towards the Communion Table as the service progressed.

[I had a related example using Rembrandt’s Prodigal Son painting and Barber’s Adagio for Strings but didn’t get to use it.]

Image as Illustration or Icon

Image as Illustration or Icon

Next we looked briefly at different kinds of images and how they function.

- Images that illustrate – someone talks about a sunset and shows a picture of a sunset. They are primarily to depict or represent.

- Images that invoke – some images do more than illustrate, they invite contemplation, wonder, or awe. In a sense, they invoke something beyond themselves. They do more than represent.

- Images that evoke – some images provoke a reaction from us, particularly those that disturb or shock us. More than merely depicting, they require a response.

We looked quickly at a bunch of images. The latter two kinds of images require contemplation, hence projecting the image for a short time simply won’t work, nor will making people physically ‘move on’ when they want to stay and look. Hence, the church needs at times to literally be an art gallery, allowing time and space for movement and contemplation. My example was to look at pictures that I had used in a Sunday service where the text was about Jesus welcoming the children. I introduced people to the work of photographer Magnus Wennman on where refugee children sleep. Click here for more photos.

Here we are beginning to see that there is a spectrum between illustration – invocation – icon – where the latter is a window to the divine. And no, i’m not an icon specialst, in fact this whole area is one in which I need to do some work…There’s quite a bit more that can be explored in this area of image in terms of sign, symbol and more sacramental representation. [I have the books…]

We talked very briefly about using more than one screen in church and having stations. I showed them my iPhone theatre box with Belkin hub for earphones (hat tip Mike Emmett).

That’s where we finished. I have loads more stuff. Edward Hall’s high-context and low-context communication. Juxtaposition and disruption. What might participation in media/communication before, during and after worship look like? Examples from Rosefield UC with Youth Room Productions, Alive@5 and our Interactive Easter and Christmas events, QR codes, mobile phone adventures, AutoRap and more.

It will take some work to prep all that for sharing. Stay tuned.

Additional references

Mary Gray-Reeves and Michael Perham, The Hospitality of God: Emerging Worship for a Missional Church, SPCK, 2010.

Tex Sample, The Spectacle of Worship in a Wired World. Abingdon, 1998.

Resources

Royalty free photos – Pexels, Unsplash, Pixabay

Short videos – Pexels

Religious Art

– Vanderbilt University Library

– Web Gallery of Art

– Methodist Art Collection (UK)

Metropolitan Museum of Art – Free Images – go to page and select “Open Access Artworks”

National Gallery of Art

Rijks Museum

Smithsonian Open Access

Art Institute of Chicago

I’d also recommend ArtWay as a great portal to explore art and religion.