Last night I hosted the first of a series of workshops for churches seeking to have an online presence through worship, as part of my current role with the Centre for Music, Liturgy and the Arts (within the Synod of South Australia, Uniting Church in Australia). We had people from nine congregations registered, seven of which are currently offering some form of worship online. Every two months we will meet at a church which is streaming a worship service, hear about the ‘why’ and ‘how’ (aims and approach) and see the ‘what and how’ (tech). I also provide input (see below) and we engage in peer conversation. It was a packed evening but we were off to a good start. Here’s a bit of an overview.

Last night I hosted the first of a series of workshops for churches seeking to have an online presence through worship, as part of my current role with the Centre for Music, Liturgy and the Arts (within the Synod of South Australia, Uniting Church in Australia). We had people from nine congregations registered, seven of which are currently offering some form of worship online. Every two months we will meet at a church which is streaming a worship service, hear about the ‘why’ and ‘how’ (aims and approach) and see the ‘what and how’ (tech). I also provide input (see below) and we engage in peer conversation. It was a packed evening but we were off to a good start. Here’s a bit of an overview.

As people arrived I had a slide with 15 minute excerpts of all of their online services looping simultaneously – without audio! (thanks Keynote and my new Macbook Pro). Understandably this caused quite a bit of conversation.

Communication and Culture

My introduction began with a brief reminder that different societies have different forms of communication – oral and sign/symbol, handwritten, printing press, electric/electronic, and digital, and that the form of communication is integral to how the society functions. Apart from the oral, these are all based on technologies of some sort. Technology is neither inherently evil nor simply neutral, but exists as part of culture and society. Lelia Green uses the term “technoculture” in her book of the same name. The production of technologies, the manner of their use in everyday life, and their outcomes are all embedded in culture, for better and worse. In this sense they can be seen as an integral part of being human: we are made in the image of a God who creates.

My introduction began with a brief reminder that different societies have different forms of communication – oral and sign/symbol, handwritten, printing press, electric/electronic, and digital, and that the form of communication is integral to how the society functions. Apart from the oral, these are all based on technologies of some sort. Technology is neither inherently evil nor simply neutral, but exists as part of culture and society. Lelia Green uses the term “technoculture” in her book of the same name. The production of technologies, the manner of their use in everyday life, and their outcomes are all embedded in culture, for better and worse. In this sense they can be seen as an integral part of being human: we are made in the image of a God who creates.

“Technology is, first and foremost, a human activity that is carried out within the context provided by God for human beings to exercise their creativity and agency.” Heidi Campbell and Stephen Garner, Networked Theology. Baker Academic, 2016.

“Technology is, first and foremost, a human activity that is carried out within the context provided by God for human beings to exercise their creativity and agency.” Heidi Campbell and Stephen Garner, Networked Theology. Baker Academic, 2016.

Communication technologies do not simply convey meaning. They are used in meaning-making, not only by the producers, but by the consumers, so to speak. Popular culture (and its artifacts) is a primary arena in which people make sense of their lives.

Peter Horsfield sees media “not as instruments carrying a fixed message but as sites where construction, negotiation, and reconstruction of cultural meaning takes place in an ongoing process of maintenance and change of cultural structures, relationships, and values.” Peter Horsfield, “Media,” in Key Words in Media, Religion and Culture, ed. D. Morgan. Routledge, 2008. p111-22.

Peter Horsfield makes a compelling case that dominant forms of cultural communication shape the form of social interaction and institutions, including religious institutions, communications and expressions of belief.

“If we think of media culturally rather than instrumentally, it can be argued that different media prefer particular forms or structures of religious faith to others. From this perspective I’d argue that the denominational structure of Christianity that emerged during the Modern period, emerged because it was the structure of Christianity most appropriate for cultures structured by printing.” Peter Horsfield, The Mediated Spirit, Commission for Mission, Uniting Church in Australia, Synod of Victoria, Melbourne. 2002. CD-ROM. [See also Peter’s book From Jesus to the Internet, Wiley and Sons, 2015.]

If this is true, it is no wonder that with the rise of digital communication at the expense of print media, social institutions including churches (and their denominations) are challenged in terms of authority, teachings and practice in a pluralistic world.

Web 1.0, 2.0 and so on

We then did a brief skate from Web 1.0 to 4.0 in terms of some of the main features.

We then did a brief skate from Web 1.0 to 4.0 in terms of some of the main features.

- Web 1.0 – Broadcast – watching, reading, searching

- Web 2.0 – Interactive & Authoring – interaction, collaboration, conversation, creation

- Web 3.0 – Distribution & Influencing – cloud, mobile devices, semantic access

- Web 4.0 – Platform & Virtual – platform consolidation, augmented reality, virtual assets, AI

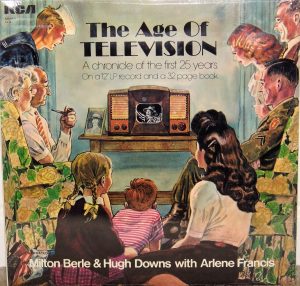

Part of my purpose here was to indicate how rapidly communication has changed since the mid 1950s, but more importantly to raise the question of whether we are seeking to use new media (eg. the internet) to do the work of old media (ie. broadcast to an audience) rather than to engage in interaction, or to recognise that people are creators of meaning and not just consumers of meaning.

Hence the first segment finished with this slide. What do we think we are doing when we are live streaming our worship? Are we merely broadcasting? To whom? Do we think of them as an ‘audience’? What do we know about them?

Hence the first segment finished with this slide. What do we think we are doing when we are live streaming our worship? Are we merely broadcasting? To whom? Do we think of them as an ‘audience’? What do we know about them?

Learning From Practice

Our hosts at Adelaide West Uniting Church, minister Lynne and producer James led us in an exploration of why they have developed a weekly, 35 minute standalone online worship service, separate from their Sunday morning worship. Their decision NOT to broadcast their weekly Sunday morning church services following COVID has been a significant decision, resulting in what they now call a ‘church plant’. See the article in the Autumn 2024 Edition of New Times.

See their Youtube Channel here.

Lynne spoke about assumptions regarding who was online (participants rather than audience), assumptions about church background (or none) and how that shapes language and ‘public theology’, and also partnerships with congregations that have developed. James did a “show and tell” about how they produce the service weekly in a tiny studio in the church building. It’s a remarkable setup. The two of them also model excellent collaboration in ministry, along with James’ studies in media as well as psychology adding a lot to the contribution of his technical skills.

This online ministry has developed further into some Q&A videos and a podcast series. It was an excellent conversation and a stimulus for many questions.

Broadcast or Engagement?

When we regathered I returned to the question of how many of our digital communications are ‘broadcast’ vs interactive engagement, and what do we think our communcation will lead towards?

What assumptions do we make about those who connect with us? Do we see them as

absent members?

absent members?- distant admirers?

- lazy Christians?

- church shoppers?

- spiritual seekers?

- spiritual pilgrims?

How does this affect how we approach and value engagement with them? How easily can we communicate across the breadth of those gathered in worship and those participating online? What does it mean for ministry and mission to see the church as part of a networked society and not as the centre of people’s lives?

I will be setting up a private web page to share resources with participants. I’ve decided against having an online conversation group at this stage, though I may invite them to experiment with me by joining an online chat medium with which some will be unfamiliar – Discord or Twitch or Spatial Chat – in order for them to see some engagement possibilities.

We finished with some small group reflection which included articulation of learnings and questions, and identifying areas that people want to explore in the future.

I concluded by speaking of our human yearning for community and reading Padraig O Tuama’s amazing poem “Sacramental” from Sorry For Your Troubles. I told some of my own story about not wanting to attend church but still needing community.

Next time I’ll be looking at research about how people link online and offline religion, plus notions of storied and constructed identities. We’ll start to talk about faith forming practices and what it might mean to engage people in them, and means of digital engagement in addition to broadcasting your church worship service. Lots to look at in the coming sessions.

The next session is planned for mid-July. Date to be confirmed soon.